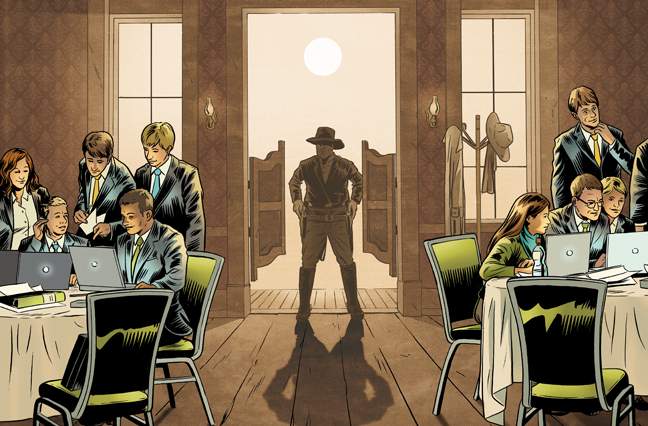

The Wild, Wild East

If it hasn’t happened yet, it will soon: A client will build a factory, set up a market, or enter into a joint venture in the booming Asian economy. At that point you have two choices: Take the plunge across the Pacific or let a local Asian broker or large international broker with overseas offices grab your client.

“When a U.S. company reaches a certain size, it will look at China, India and Southeast Asia,” says Lawrence Adam, COO of Sterling Knight, The Council’s first Singapore-based insurance broker. “Countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam have become centers of global manufacturing and are becoming huge markets.”

And that “certain size” doesn’t have to be large. More than 97% of U.S. exporters employ fewer than 500 people, according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

“We want to sell you all kinds of stuff,” President Obama joked to Hu Jintao during the Chinese president’s visit to the White House in January. That meeting followed Obama’s November visit to Asia, at which he and 20 other world leaders proclaimed “The Yokohama Vision” of an Asian-Pacific free-trade zone.

AIG was one of the first in the insurance industry to go East, establishing a foothold in the delicate business culture decades ago. Other business leaders, like Warren Buffett, are now entering the Asian market. His American-based Berkshire Hathaway started selling car insurance in India through an Internet portal and telemarketing, the same tactics that made his Geico subsidiary America’s third-largest auto insurer. During Buffett’s first visit to India, earlier this spring, investors had the opportunity to meet him in New Delhi—if they shelled out $48 for car insurance.

BALANCE IS SHIFTING

The U.S. economy is still three times larger than China’s, but the balance is shifting. Asia encompasses nearly 30% of the world’s land mass and, with nearly 4 billion people, close to 60% of the world’s population. Since 2005, according to insurer FM Global, the average growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) of China and India has been twice that of Europe and the U.S. And Asia is in need of insurance. Allianz Asia Pacific, already represented in the Far East, saw profits grow by nearly 50% last year. This is an industry in which the U.S. and other Western nations can export their resources and knowledge of workers comp, health and property-casualty.

“People forget that insurance is still new in this part of the world,” says Duy Nguyen, director of Asia/Pacific operations for Honan Insurance Group, “and most clients still do not know the difference between agents and brokers.” For example, he says, most restaurants in Asia don’t carry liability insurance.

While North Americans spend 4.5% of their GDP on non-life insurance, the Chinese spend only 1.1%, and Indians even less, according to FM Global. Asia endures 43% of the world’s catastrophes—the recent Japanese earthquake is the fourth-largest ever recorded—but less than 10% of the country is covered by non-life insurance. In contrast, North America experiences 19% of catastrophes, nearly half of which are insured.

“These markets are hungry for industry expertise and experience in large complex risk placement,” says Cheok Chin Hock, head of client relations for Southeast Asia with Asia Capital Reinsurance Group.

An exciting market? Yes. An opportunity to jump in with both feet? Not exactly.

The sheer size of the market poses a challenge: The archipelago of Indonesia alone has more than 17,000 islands, 6,000 of which are inhabited. The geography ranges from the highest point on earth to thousands of miles of fragile coastline. The climate ranges from some of the world’s coldest places to its hottest and most humid.

Cultural and economic diversity pose even more of a challenge. Asia’s land mass consists of 48 countries, and a behemoth such as China can vary from cosmopolitan to clannish in its 22 provinces, four municipal districts, five autonomous regions, two special districts and Taiwan, which is claimed by China. Drive across the bridge from sophisticated Singapore to the gritty factory towns of Malaysia, says Julian James, CEO of Lockton International, and “you are looking at a vastly different market.” As with most developing areas, protectionism is standard practice, and not obeying the rules, or what the local authorities perceive to be the rules, can leave an unwary Westerner behind bars.

“Asia is like the Wild West in the 1800s,” James says. “Except…we’re going east.” What follows are some valuable lessons from brokers who have been there already.

COMPLIANCE IS RULE NO. 1

It could be said that, in Asia, all insurance is local. In some instances, insurance is political, and whom you know isn’t just important, it’s critical. “If you start talking to a factory owner about his suppliers or subcontractors, he’ll say ‘my brother, my friend,’ and there is always someone attached to the Chinese government,” says David Melendez, senior vice president of product development of Bravo Sports, who’s spent 15 years working with Chinese manufacturers. “You’ll find the factory owner is probably a politician. One ‘clan’ I deal with makes skateboards for us but is also into real estate and water treatment. And they also act as a bank for each other.”

There’s an upside to the close-knit nature of Asian business, say those who know it well: Once you make a friend or a business partner, they are a friend for life.

“One needs to find the right partner to ensure it is a long-lasting and equal cooperation,” says Raymond Chow, managing director of Houlder Insurance Brokers Far East Ltd., a subsidiary of a Chinese government-owned group that is ranked No. 7 in profit generated to the government.

This clannishness reaches the top of the economic ladder. When President Hu met with President Obama, the New York Times noted that trade restrictions, state subsidies to favor domestic companies, and indigenous laws meant to favor homegrown businesses stood in the way of American businesses wanting to enter China.

There are some signs of improvement; the new Shanghai insurance exchange says that it will admit Western companies, but it hasn’t said how many or which ones. On the other hand, when the World Economic Forum surveyed more than 1,300 business leaders for the most problematic factors of doing business in Asia in 2009, “inefficient government bureaucracy” was at or near the top for virtually every country with the exception of Singapore and Japan, according to Runckel & Associates’ website Business-in-Asia.com.

So what should a broker or insurer do? Never forget that compliance is rule one. “One false move and you could be fined by a local regulator, which could hurt a U.S. broker’s reputation,” says Sterling Knight’s Lawrence Adam.

HEADS YOU WIN, TAILS YOU EAT

The language barrier can also be difficult to overcome, particularly when you factor in the time difference of nearly half a day when calling India. “It can be a nerve-wracking experience,” admits Sandy Pelzek, a vice president with Hays Companies of Wisconsin who has focused on multinational clients for 11 years. She has learned to pick up bits of local languages from free translation sites and conducts much of her business by e-mail. “You must clearly communicate what you expect the local broker to provide,” she says, and allow for the fact that insurance terms like “excess” can mean different things in different regions.

To prevent confusion, it may be necessary to stay up late, get up early, and “pick up the phone.” Calling an in-country broker can also be difficult as employees there shout around the office looking for someone who speaks English.

But language is only one challenge. In China, for example, a direct question doesn’t always elicit a direct response. The local broker or agent may try to save face in front of peers by giving you the answer you want to hear, so it’s important to circle back to see if the broker can really fulfill his or her commitment.

And the cultural differences extend beyond language. Melendez, of Bravo Sports, will never forget the time he was served lobster in an elegant Chinese restaurant. “They brought out a live lobster in a bowl of ice, cut him in half in front of me, and put both halves in the bowl facing up,” he recalls. “I was eating his tail while he was looking at me.”

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEW

Americans have to deal with Asians as equals, and in some instances, as a dominant force. Rapid economic growth has enabled Asia to accumulate more than $4 trillion of foreign exchange reserves, roughly half the world’s total, according to FM Global. As a result, FM’s staff members in Asia “do not wear big, clumsy shoes and clop around the place, sticking flags in the earth and staking out territories,” wrote managing editor Bob Gulla in a recent issue of Reason, FM’s magazine. They act more like “Zen gardeners,” Gulla wrote.

“The old status quo of a very dominant America and a very subservient Asia has gone,” said Simon S. C. Tay, chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, in a speech to the Asia Society last year. “We have to look forward to…a new relationship.”

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s business partner, echoed that statement last year at Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting. “Asians will get way more important in the world,” Munger told stockholders. “We in the West should not rush to apply our own standards to them.”

One thing everyone agrees on: In China—unlike the U.S.—the trains run on time.

A WIN-WIN SITUATION

Brokers say it helps to immerse yourself in local culture and learn the language, but small mistakes in etiquette will be forgiven if you add value. One way to do this is to provide Asian partners with a window on the wider world and underpin local markets with international experience. “A U.S. broker can shine by not just providing accurate advice,” says Adam, “but accurate advice in the U.S. context.”

Take the case of the Singapore firm that was bought by a U.S. company with a U.S.–based broker who was unfamiliar with the Asian market. The U.S. broker had a Broker of Record (BOR) letter stating that it was taking over the Singapore firm’s insurance account. But having worked with its local broker for about 15 years, the Singapore firm was reluctant to work with the U.S. broker.

Since the policies being issued were part of a global umbrella program, some of the new local policies would cost nearly 10 times as much. And the additional expense would be borne by the Singapore firm and not the acquiring U.S. company. Given these circumstances, the Singapore firm didn’t see any benefit, preferring instead to retain its existing insurance program and its existing broker. If the merger integration was not handled smoothly, Adam says, the U.S. company’s takeover could be construed as “aggressive.”

To counteract this, Sterling Knight took the following steps. First, it demonstrated “mutual respect” for the Singapore client by not initially showing them the BOR letter, which appointed the U.S. broker and cancelled the local broker. Then it mediated with both sides—the U.S. company and its U.S. broker, and the Singapore firm—by holding meetings with both top and middle management. Once it understood both the U.S. and Singapore companies’ viewpoints, Sterling Knight conducted an audit of the Singapore client’s insurance program and followed up by demonstrating how it could save money by eliminating duplication and plugging coverage gaps. When Sterling Knight had shown “mutual respect,” it presented the BOR letter—which was accepted—and the takeover was complete.

USE THE NETWORK

Bear in mind that things don’t always go so smoothly. When doing business overseas, a U.S broker may not have any other option but to play the hand they are dealt and work with the local Asian broker who handles the local company’s account.

Simon Weaver, managing director of major corporate risks at Jardine Lloyd Thompson Asia, suggests asking these types of questions to vet the local broker: Is the local brokerage firm up to international standards; is it within reasonable travel time of the client’s location; is the broker carrying adequate professional indemnity protection?

“Some countries in Asia have brokers’ associations, such as The Hong Kong Confederation of Insurance Brokers,” says Weaver, “and U.S. brokers should ask if their proposed partner is a member of their local association.” If the local broker doesn’t pan out, it may be helpful to ask a trusted insurer for a recommendation.

Another alternative is to join an international organization that includes both American and overseas brokers and develop personal relationships with those in Asia. You then share the business with that local overseas broker in the network instead of losing the client’s business to another broker. Such relationships are the backbone of international networking groups such as The Council’s Global Connection (to learn more, visit the Council’s website, www.ciab.com).

“The Council has 40-plus non-U.S. members,” says Coletta Kemper, the Council’s vice president of industry affairs. “Servicing through a broker network can be just as effective as being there. The local broker is on the ground and has the local knowledge and expertise to service the client’s business effectively.”

New members of The Council, such as Gautam B. Boda, managing director of J. B. Boda Group in India, are ready to help. “We have been actively supporting many large and mid-sized brokers and servicing their clients in India,” he says.

Whichever path a broker takes to Asia, there’s still no substitute for experience, says Julian James, who has traveled the world for nearly 13 years, first for Lloyd’s and then for Lockton. His advice to any broker who wants to do business in the Wild East: “Get on a plane and go there.”