From Trading Floor to Keyboard

To reach the office of the chairman of Lloyd’s of London, you must cross the cathedral-like room known as the Lloyd’s trading floor. It’s early afternoon when I pass through, so the usual buzz is absent. Only a few juniors with gourmet takeout sandwiches are on the box (in the underwriting booths).

But when a crimson-clad waiter shows me to Bruce Carnegie-Brown’s office on the 12th-floor pinnacle of the corporation, Lloyd’s new chairman is at his desk, sans sarnies. He’s meeting me at lunchtime, but we’re not having lunch.

“There’s not much time in the day,” the affable and clearly clever Carnegie-Brown declares. “Insurers have been slower to give up on lunch than other parts of the financial services market, but I did quite a long time ago in the interest of greater efficiency.”

Indeed, efficiency is the current holy grail for Lloyd’s. Clobbered by costs, everyone is clamoring for efficiency. The companies that comprise the market are investing in it, and joint market initiatives are attempting to drive it. My first impression is that Carnegie-Brown is a man well suited to the leadership of Lloyd’s efficiency drive.

Tech-Driven Efficiency

Back in 2003, when he began a brief stint as president and chief executive of Marsh Europe, Carnegie-Brown said the future of London wholesale broking, and thus the Lloyd’s market—which is dependent entirely on broker distribution—rested on its ability to embrace technology. Nearly a decade and a half later, the same market faces the same challenge. Only about 10% of market business is placed electronically, although the need to go digital is more pressing than ever.

“I am somewhat surprised by how resilient the Lloyd’s model has been, because clearly it has prospered in the absence of making a much more radical transformation,” he says. Outside the high-value, high-complexity end of the insurance market, dramatic change has happened since his time as leader of one of Lloyd’s largest brokerages. Online selling has driven almost complete disintermediation in U.K. personal lines, for example. It’s a subject Carnegie-Brown knows a lot about. Alongside his Lloyd’s job, he is chairman of Moneysupermarket, an online financial services aggregator listed on the London Stock Exchange.

“The most differentiated value of a broker is the provision of advice, and when you’re buying motor insurance, you don’t need advice,” Carnegie-Brown explains. Today in the U.K., more than 70% of consumers buy their auto cover online, most through aggregation websites. Within the space of a minute, they get scores of insurers bidding for their business. “Even the most efficient broker would struggle to compete with that level of efficiency and responsiveness,” the chairman argues, “but the high-complexity lines like aviation, marine, catastrophe and cyber insurance haven’t changed nearly as quickly.”

Not yet, he says, but change must come, even in Lloyd’s complex sweet spots. Expenses are too high and competition too fierce for the plodding old ways of Lloyd’s, where brokers still wait in queue to make their pitch to underwriters, to continue in the age of technology.

“Everyone I meet agrees that the future of the Lloyd’s market relies on our adopting more efficient ways of working and better technology to execute them,” Carnegie-Brown says. “It is a natural occurrence in the evolution of markets. They become more efficient over time. Inefficiency gets squeezed out. If we remain inefficient, we will become uncompetitive.”

The goal isn’t new for Lloyd’s, but so far every comprehensive attempt to modernize the placement process has failed at the implementation stage, despite the millions London has splurged on tech since the 1990s.

Carnegie-Brown ran Marsh Europe after the failed revolution of Electronic Placing Support (EPS), the London market’s first concerted attempt to join the digital revolution. When EPS simply wouldn’t stick to the wall, the biggest brokerages launched their own electronic trading platforms. But proprietary systems created fiefdoms, which don’t suit the subscription nature of the London market. Since then, things have changed. “The risks of technology transformation are reducing,” Carnegie-Brown declares.

A decade ago the insurmountable challenge was to get everyone to sign up to a single, marketwide approach. Today, efforts to create an open-architecture environment for London’s commercial insurance business should remove the competitive considerations from the market’s uptake of sophisticated IT solutions.

Carnegie-Brown’s technology vision is nuanced differently from his predecessors’ programs. He doesn’t see any single market system as the answer. His goal is more fundamental. “The challenge is to ensure we move from an analog market to a digital market,” he says. “Once there, everyone has a huge number of choices about the applications they use and how they run their businesses.” If any compulsion is involved for those trading in the Lloyd’s market, it will be a means to that end and will be imposed only to drag the laggards along.

Herding cats can be easier than creating consensus in Lloyd’s, even for its chairman. His job is to run the market, not the market’s businesses. He heads the central facilitator, which has provided market infrastructure since 1769, but he has only limited control over how the constituent underwriting players—Amlin, Beazley, Hiscox, Catlin, Kiln and scores of others—manage their own affairs, let alone their systems and data.

He has even less authority over the brokerages. Central strategies have not always been welcome. Market cohesiveness has been greater and growing since Lloyd’s escaped from the perilous brink of collapse in the 1990s, but decrees don’t land lightly.

But like others, Carnegie-Brown believes the modernization prize is too big to shy away from. Conversion to a digital market will bring enormous value, as it should strip away much of the vast cost associated with business processing.

“Data input just once can be used by different market participants in different ways for the different functions of their business,” he says, listing a few examples. After entry, digital information can be used to settle an insurance premium through a foreign exchange transaction or to inform an underwriter’s risk model. A reinsurance broker can use digital information to aggregate a customer’s risk portfolio. “The data is adaptable in digital form,” Carnegie-Brown says. “Ensuring that all of our data is digital has to be the overarching strategy for Lloyd’s. People can then engage with it in the ways that they choose.”

Which brings him back to the topic of efficiency. Digitization, he says, is “part of improving the efficiency of the market: reducing errors, cutting costs and improving the value of our ability to use the data that we have.”

Fundamentally, the value propositions presented by both underwriters and brokers will remain the same, he says, but will get more of the attention they deserve in a digital market. “The huge value in what brokers do lies in providing advice to their customers on risk-management strategies, part of which involves the placement and transfer of risks into the insurance market. That won’t change.”

The same, he says, is true for underwriters, whose huge value lies in deploying their experience and data to make informed decisions about risk pricing, capital allocation management, which risks to write and which to refuse. Digitization won’t change that either, he declares.

What will change is all the activity that does not add value. For example, Carnegie-Brown says, “Brokers and underwriters—the people who provide the advice that clients desire—spend too much of their time on unnecessary processing.”

Normally mild-mannered, Carnegie-Brown seems almost offended by this injustice. “The whole process of change is about eliminating the low-value activities that contribute substantially to very high costs in the insurance industry as a whole,” he says.

Global Strategy

Then there’s relevance. The Empire is over. Wooden ships sunk. Bringing risk to a pinstriped man in London is no longer the only option. Alongside efficiency, relevance is Lloyd’s next great challenge. Market insiders have been searching for ways to remain relevant for nearly as long as their quest for efficiency. “We start there already, with Lloyd’s as a global market leader in a whole variety of specialty insurance lines,” Carnegie-Brown says. “Part of the mission is to preserve that status.”

The challenge isn’t child’s play. The world is Balkanizing, he says, with rival insurance hubs growing in places like Miami, Dubai and Singapore. “Lloyd’s challenge is to make sure the business, which historically has always come to London, doesn’t get disintermediated into other centers,” he says.

Carnegie-Brown wants Lloyd’s to change from what he calls a “Walmart model,” one based on a physical footprint, to an “Amazon model,” where flag-planting is deemphasized in favor of a product focus supported by digital distribution. He has already announced that Lloyd’s will rein in its recent near-frenetic establishment of underwriting platforms around the world, which was part of his predecessor’s “Vision 2025” relevance strategy. In Carnegie-Brown’s view of the world, getting closer to the customer (another insurance industry trope) does not necessarily mean physically closer.

Carnegie-Brown would approach Lloyd’s clientele through monitor and keyboard, or maybe smart phone. “We have a central nervous system here in Lloyd’s, with an incredible resource of skills, of data, of expertise,” he says. “We have an opportunity to deploy that resource into new parts of the world, and to do so differently in our existing markets, to make our products available to more customers, and to make them more relevant in new geographies.”

The technology is readily available to make Lloyd’s easily accessible to people in remote locations, he says. “That’s quite a different way for the international insurance industry to look at the distribution of its products,” he admits.

Lloyd’s, through its member firms, already employs some of the most sophisticated internet distribution in the sector, but it remains a very traditional market, and brokers really do still queue up to see underwriters, sometimes laden with foot-thick piles of paper in their slip cases (although the successful implementation of electronic claims filing more than a decade ago has cut many of those large bundles down to size). Late adopters will be coached, tempted, goaded and ultimately shoved into the digital age.

In this, as in all that Carnegie-Brown has to say, his views chime with those of most broking and underwriting executives at the leading edge of Lloyd’s. The urge to remain relevant through modernization while exploiting technology to garner efficiencies propels a large proportion of market companies’ agendas. Another driver is the hope of selling more cover to existing clients.

“The level of underinsurance around the world, even in rich economies, implies people don’t find value in the insurance product. That is one of the reasons they don’t buy it.”

Lloyd’s new chairman acknowledges underinsurance is driven by many factors, but he rates the value proposition as “significant.” It is partly a marketing problem. “We have to do a better job as an industry, as advocates of the purpose and value of our products,” he says. Insurers help to put peoples’ lives back together after a crisis, but, he says, that role often goes unpublicized. “We talk about the transactions and the negotiations, about minutiae, without recognizing the bigger picture, without mentioning what we do to help rebuild people’s lives and livelihoods,” he says.

More than just talk is required, Carnegie-Brown concedes, if insurance is to appear more attractive. “It will look like good value only when its cost structure is improved so that more of the premium people pay buys risk protection,” he says. “We ought to do a better job of focusing outwardly on the solutions we, as an industry, can provide to our customers.”

The Inside Outsider

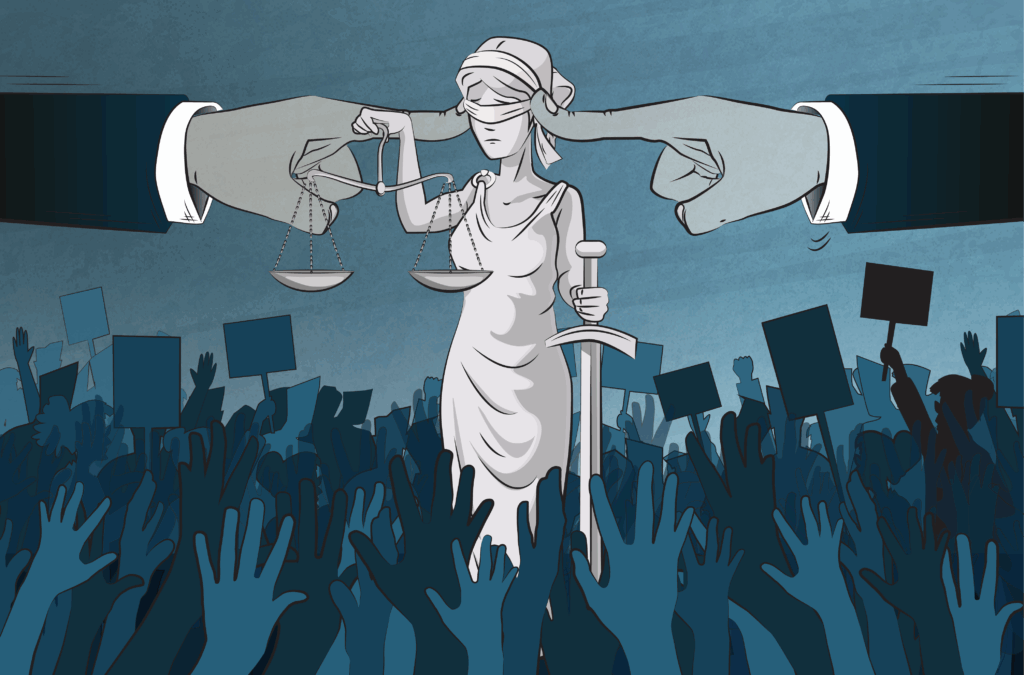

Many challenges lie ahead, but Carnegie-Brown may just be the right man for the job. He is broadcasting on the same frequency as much of the rest of the market and has the outward credibility to carry it forward.

Many in Lloyd’s had wanted his job to go to an insider, someone weaned in the cathedral-like room, especially after outsider chairmen held the post for nearly two decades. Many thought the city grandees who came before Carnegie-Brown just didn’t get Lloyd’s. But others argued that was the whole idea—that outside eyes would help the market to navigate the radical change reshaping the international insurance environment.

Carnegie-Brown, a banker by background, is insider and outsider after his stint at Marsh and subsequent board-level roles at Aon and JLT and at the Lloyd’s underwriting agency Catlin (whose eponymous founder Stephen Catlin was a popular insider candidate for the chairmanship).

“Any organization looking for a chairman will discuss whether they want an insider or an outsider,” Carnegie-Brown says. “Happily, I am both.” He says he aims to bring a breadth of perspective. His work at Moneysupermarket, he says, informs his thinking about the transformation, over several years, of the commercial insurance model intended to bring efficiency and relevance to Lloyd’s.

Further, his roles in asset-management businesses have left him with an understanding of the centrality of investing that lies at the heart of underwriting. He also knows regulators, which Lloyd’s, with more than 200 insurance licenses, has in abundance.

“A big part of the role of the chairman of Lloyd’s is to provide market oversight from a regulatory perspective and to be the person most accountable to the external regulators, in the U.K. and internationally,” he says.

And he has a few words for the U.S. broking fraternity: “Lloyd’s is open for business. We are enthusiastic to expand our business in the United States, which is our single most important market. We are working hard to ensure access to Lloyd’s gets easier, more efficient and lower cost and that we continue to earn our very strong U.S. reputation as an innovator and a payer of claims.”

Leonard heads the Leader’s Edge Foreign Desk.