Pushed Out of Network for Behavioral Healthcare

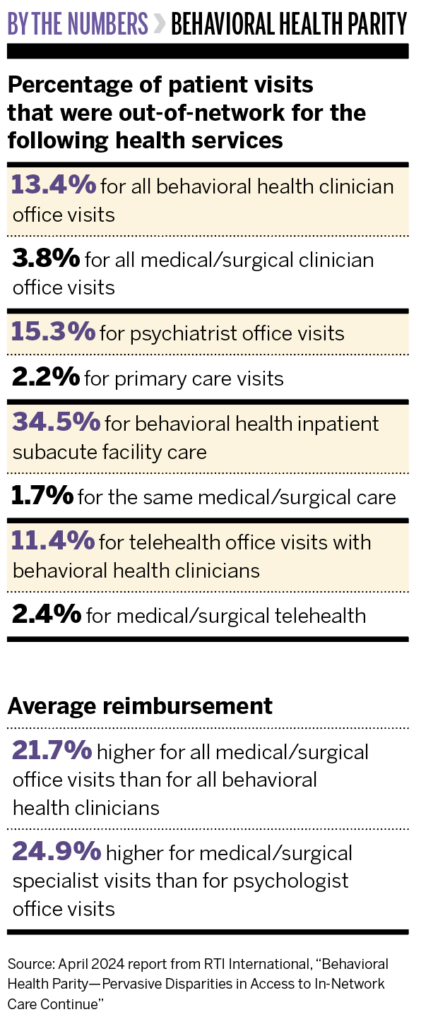

An April 2024 report from RTI International says in-network behavioral healthcare is hard to find and, therefore, consumers pay significantly more out of pocket for this care than for medical and surgical services.

HARBIN: We wanted to follow up on a report the Bowman Family Foundation commissioned from Milliman that was issued in 2019. It covered similar measurements of almost 30 million commercially insured lives from 2013 to 2017. It showed significant disparities in access between behavioral health and medical/surgical care, and we approached RTI to provide additional data from 2019 to 2021. This report was from a large commercial database with over 22 million people.

The second purpose was to see if there had been any improvement—we found there [was] hardly any—and to broaden the types of measures and analyses. We wanted to use different ways to measure provider reimbursement, not just looking at the averages but at the higher ends of reimbursement. And we wanted to compare subspecialty providers on both the medical and mental health side. We also looked at tele-mental health versus medical telehealth and in-person care.

MARK: Let’s say you hire a broker to help you find insurance for your employees, and you think you’re giving them mental health and substance use disorder treatment. Then your employees start saying they can’t find anyone who will treat their child at a residential facility or can’t find a psychiatrist and couldn’t get care. Or they did get care but had to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket. As an employer, you’re not really providing the benefit that you thought you were or that your employees thought they were getting.

HARBIN: This leaves the burden on the consumer, the patient who has got mental health or substance use problems. When they try to access insurance, the financial burden on them is significantly higher than it is for a medical/surgical patient getting care. It’s a significant problem, particularly if you look at inpatient care. We found that almost 30% of behavioral health patients had to go out of network for residential treatment. The bills for that one episode might be $20,000 to $40,000, depending on how long you stay. What person could possibly pay 50% of that cost? Then, out-of-network use on the medical side for inpatient care is like 3%.

The results we found underestimate the problem. This study included HMOs and PPOs, but some HMOs don’t have any out-of-network benefits. So, when you’re measuring claims, there are people that are going out of network and paying 100% out of pocket, but it wouldn’t show up in this study.

HARBIN: We have seen a few employers that do require this [network access] data and act on it, and they can make a big change in access. But they have to ask for it and specify the methodology, or they won’t necessarily get the full picture. Employers have a unique role to play in this because self-insured employers are liable for the behavior of their third-party administrator. They have a lot of power, and I think part of the value of this report is you can translate this into specific quantitative templates.

MARK: We tried to make it very clear in this report. You can hand the methods section to the broker and ask for your percentage [of patients who go] out of network and reimbursement methodology. You don’t just want to see a book that shows all of the psychiatrists that participate in your network; you need to see how many of your employees and their families are going out of network.

MARK: We hoped that the disparity in in-network use would have been reduced when we expanded telehealth, but we don’t see that. We see huge disparities. Insurers just don’t have large enough networks, so telehealth is not a panacea.

HARBIN: Tele-behavioral health has been an important addition for access, but we were shocked. I know a lot of plans were trying to lean over backwards during COVID to make more behavioral telehealth in-network. But there were actually worse disparities compared to in-person care in 2021.

MARK: We found, on average, that the medical/surgical side was reimbursed 22% higher than behavioral health clinicians. You can slice and dice the data in a lot of different ways, but one comparison that we thought was particularly striking was the reimbursement for common codes. Physician assistants and psychiatrists use E&M [evaluation and management] codes when they do a brief evaluation and provide a psychiatric medication. We found for that code, on average, physician assistants were paid more than psychiatrists. So a midlevel-trained medical professional is getting paid more than an M.D.-trained specialist.

HARBIN: This study also looked at the higher levels of reimbursement, which hasn’t been reported before. What it showed is that, at the 75th percentile of reimbursements, medical/surgical is paid 48% more than behavioral health providers and, at the 90th percentile of reimbursement, they are paid 70% more.